Advertising

Supported by

His decades-long efforts to maintain the colonial buildings of a capital city have turned an old slum into a tourist destination and a capitalist success.

By Steven Kurutz

Eusebio Leal Spengler, who led an effort to maintain Old Havana, transforming this historic district from a forgotten slum into an architectural gem and tourist destination, died July 31 in Havana. He’s 77.

His death reported through Granma, the official journal of the Communist Party of Cuba. In recent years, he had been treated for pancreatic cancer.

In a statement, Cuba’s President Miguel Díaz-Canel told him “the Cuban who stored Havana.”

Mr. Leal began his preservation efforts in the 1980s, when the old center of the capital was in ruins. Residents lived without indoor plumbing or reliable electricity, trash piled up on the streets, and 250-year-old buildings collapsed before their eyes.

As a historian and director of the Havana City Museum, Mr. Leal is passionate about safeguarding Cuba’s architectural history. Once, he lay in front of a steamroller to save the pavement of a colonial-era wooden street. Thanks to its campaign, Old Havana was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982.

But the lack of budget hindered Leal’s ambitious recovery projects until the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union collapsed and Cuba lost millions in subsidies. Outside the economic crisis, Cuban leader Fidel Castro, with whom Mr. Leal had befriended, gave him unprecedented authority to collect taxes and tourist profits in the old center.

Through a state-owned company, Habaguanex, Mr. Leal has invested cash in structure projects. He has restored sublime squares, Baroque cathedrals, restaurants and hotels of the eighteenth century, adding the hotel Ambos Mundos of pink, where Ernest Hemingway wrote “By whom the bells bend”. Paradoxically, Old Havana was a capitalist success: the restored buildings attracted foreign tourists, whose cash then financed more recovery work.

By the mid-2000s, about three hundred buildings had been renovated, about one-third of those in Old Havana. And Leal, who hired 3,000 employees at the head of the Office of Historians, was hailed as a hero and a style of role for environmentalists around the world.

“He was an exclusive figure for his time,” Jeffrey DeLaurentis, an American diplomat who served in Cuba under the Obama administration, said in an interview. It has also enjoyed autonomy. He was very new to the Cuban system.

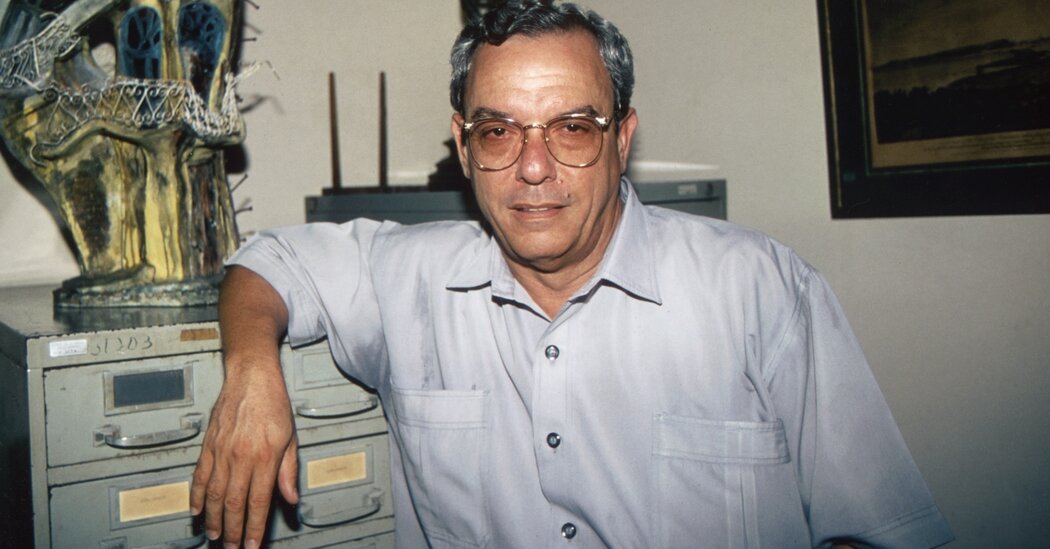

As Old Havana has become an economic engine for Cuba, Leal is known as its unofficial mayor. He greeted followers in the streets (usually in his burocatically grey guayabera shirt). He starred in a television series about the history of the capital, “Walk Havana” (“Paseo Habana”). He has lectured at American universities and approached him through newshounds as a prominent public intellectual.

The renovation of Old Havana, however, comes at a cost; some citizens were displaced when overcrowded buildings were modernized. Preservation also had its limits. Visiting journalists, who added one from the New York Times in 2007, noted that Old Havana had as a film set, quite a facade, while a few blocks away, deficient Cubans lived in decrepit buildings. Luxury hotel workers earned through a state salary of $20 a month.

As Leal al Times himself said, the revitalization of Cuba’s colonial architecture has done much to solve more important social problems. “It pains me to see each and every day the border that separates what has been restored and what remains to be restored,” he said.

Eusebio Leal Spengler was born on September 11, 1942 in a working-class community in Havana. He was raised through his single mother, washerwoman and housekeeper, and dropped out of sixth grade to help the family. No other information was available about his mother or father. The survivors arrive with their two sons, Javier Leal and Carlos Manuel Leal.

After the 1959 revolution brought Castro to power, public education in Cuba became free. In 1975, Mr. Leal earned a bachelor’s degree in history and then a doctorate. Sciences, University of Havana. But he had been self-taught from a young age, spending his young people in libraries reading about history and architecture. In the early 1960s he appointed an apprentice in the office of the historian, led at the time by Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring.

After Roig’s death in 1967, Leal assumed the role and oversaw the renovation of the 18th-century governor’s palace in a museum, his first recovery project.

“By ancient tradition, each and every ancient people in Latin America maintain the institution of the ‘chronicler’, which carries the call of life to save the reminiscence of the people,” He told Smithsonian magazine in a 2018 profile.

But Leal didn’t need Old Havana to be a mummified city for tourists. He used some of Habaguanex’s profits to build schools and fitness clinics and fix apartment buildings so that former citizens can stay. As he told The Washington Post in 2000, he took care to create “spaces of silence” in his plan: living in neighborhoods away from hordes of tourists.

Your good luck has brought you political influence. As a practicing Roman Catholic, he sought relations between the Catholic Church and the Cuban authorities, which had dispelled priests after the revolution and had officially embraced atheism. When Pope Francis visited Cuba in 2015, Leal gave him a tour.

From building to building, block to block, he continued his preservation efforts until the end of his life. One of his last and greatest ambitious projects is the recovery of the National Capitol Building, which, with its vaulted ceiling and neoclassical architecture, resembles the capital of the United States. It opened in 2018 after 8 years of work.

“What we’re doing here is keeping the heritage, reminiscent of the Cuban nation,” Leal told The Times in 2005.

“I probably wouldn’t see the full recovery of the city,” he added. “There’s still a lot of paintings left, but it’s a start.”

Advertising