While control says a rights offer is underway, some say a hesitant Sasol can still pull a rabbit out of the hat

The pandemic has led to a resurgence of plastic waste, but it also results in a systemic restart.

The poultry company considered rejects Country Bird Holdings shareholders to seek representation on the board

Transnet CEO Portia Derthrough, tasked with straightening a state-owned company unearthed through corruption

We have evolved to unite, socialize, commune, so why does an invisible terrorist take that away from us?

Horror films provide surprising, if not unexpected, information about the course of the plague in which we are involved. Death, isolation, worry and paranoia are essential elements of this kind, as in pandemics.

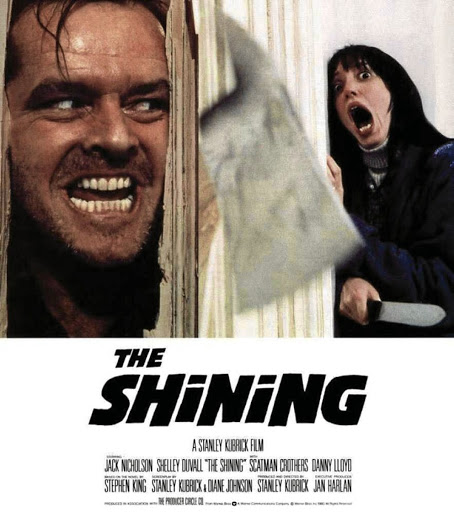

Three films give us other perspectives on the plague. The seventh seal, almost a horror film, is an existential meditation; The Last Man on Earth depicts the horror of a plague unfolding, while The Shining is a mental examination of a circle of relatives in a lockout situation.

“When I was born in 1918, my mom had Spanish flu.” Thus begins The Magic Lantern, the autobiography of Ingmar Bergman. He himself nearly died, but he was cared for by his grandmother, and has since been persecuted by the perception of death. “For as long as I can remember, I had a dark concern about death, that puberty and early twenties became unbearable.

Bergman’s films are almost about the struggle to find the meaning of life, and this is the central theme of the Seventh Seal. A knight, Antonius Block, returns home after the Crusades during the Black Plague in the mid-14th century to save his marriage, but is doomed to die before he can try.

In an unexpected strategy, death is depicted in the film through a figure dressed in black, his face painted white, rising above the living. When death seems to be blocked at the opening of the film, the knight defies death to a game of chess that will mark his destiny. Therefore, you have time to complete your search for meaning to life.

Block laments that he has defected through God, who remains silent and absent. “It’s like there’s no one there.” He needs God’s direct wisdom. The film takes its name from the Book of Revelation, which speaks of the breaking of the seventh seal, from which Block expects to be informed of the secret of existence. But you’re never informed of the secret.

Although the plague is not in the middle of the film, death is; however, the plague is the horizon. It is also the cause of many occasions in the film, such as the identity of a 14-year-old woman as a witch, who is accused of the disease and set on fire. In the scene, Jof the clown is humiliated through the other people of an inn, his cruelty is a brief respite from anxiety.

Priests have made a decision about what other people did with the plague, just as our scientists do today, who would possibly be as ignorant as the priests at the time. One artist claims that the plague is God’s punishment while painting scenes of frantic self-flagellation and death stalking the living.

Block loses his chess match to Death, which is not true, however the knight saves the clown’s life and his family, a measure of salvation. The film ends with Death and his accusations doing a joyful dance.

Critics saw the film as an allegory of concern for the atomic bomb, as the Cold War unfolded, a kind of plague.

For Bergman, described through Woody Allen as “the poet of mortality”, the plague is still there, of the human condition, death awaits us all.

Memories

Another film is Sidney Salkow’s low-budget, The Last Man on Earth, founded on a novel by Richard Matheson. The film has become a kind of style for zombie and undead movies, although the genre preceded the film.

It opens with desolate apartment block shots in a U.S. city (although filmed in Italy), the music weeds a haunting atmosphere. Empty streets, deserted cars with wide open doors evoke death before even seeing bodies strewn across the sidewalks.

In September 1968, Vincent Price played Robert Morgan, the only survivor of a global scourge, who had been living a lonely life for 3 years. But he is not alone, because the earth is pierced by the inflamed: vampires who only emerge at dusk because, like Dracula, they cannot the sun. They can’t help mirrors or garlic either. This excessive symbol of social estrangement turns the inflamed into inhumane, or even some other species, a ray of stigma practiced today.

Morgan’s regimen is to “go to work” every single day in search of and destroy zombies, and get food and supplies. We stick to it while selecting fuel, food, mirrors and garlic, just as we do now in common supermarkets, gaining a convenience of supply. After a day’s work, he barricades himself in his suburban home for 12 hours of lockdown.

With no one to communicate with, Morgan speaks to us, the spectators, as if he were delivering a monologue. When he thinks he has to hold on to reason, which he thinks takes him away from zombies, one wonders about his intellectual health.

In a series of flashbacks, we see how the scenario happened. An unknown disease occurs that kills other people after blinding them. Foreshadowing Covid, Morgan and his fellow scientists speculate on how the plague is transmitted, whether it is transported through the wind. Morgan’s wife and daughter are inflamed and pray for a vaccine as the government announces a state of crisis and bans meetings.

The removal of the dead becomes both a logistical and humanitarian problem, and the marks of civilization are eliminated one at a time.

Finally, Morgan dies through a species that has transcended the zombie world and has more, though not quite, humans: they are the future.

Since then, several remakes have been made: Omega Man, starring Charlton Heston, a mediocre and turbulent performance, while I am Legend, starring Will Smith, turns loneliness into a party, according to a critic.

Shine

For natural horror, it’s hard to overcome The Glow, a film that isn’t yet about the plague about the cabin fever, or how we might respond to the closure. Based on a novel by Stephen King, Stanley Kubrick opens his film with the haunting music of Wendy Carlos, his edition of Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), a 14th-century Roman Catholic requiem mass devastated by the plague that also appears in The Seventh SealArray.

The glow was criticized through critics after its release in 1980, but has since been identified as a masterpiece of the horror genre. In the film, Jack Torrance (a maniac of Jack Nicholson), his wife Wendy (a little Shelley Duvall) and their son Danny live remotely at the Overlook Hotel, where Jack loses his mind and tries to kill his family.

With a script almost composed of non-events, the film has provoked massive hypotheses about hidden meanings. Some read that the hotel, built on the site of a Native American cemetery, symbolizes powerful, secret and corrupt America, and alludes to a founding genocide. Much of this reflects how history underlies and exacerbates inequality, and the deficient suffer the worst of spell crises, as we note with Covid-19.

But it is the dynamics of isolation that captivate us. Jack slowly comes out of his brain looking to use isolation to write his wonderful American novel. When Wendy discovers her “first draft,” a bunch of pages that repeat a bachelor phrase, “All the paintings and no games make Jack a boring kid,” all hell goes crazy. This line condenses all the bitterness of Jack’s soul, which he attributes to his family, seeing her as the source of his failure and misery.

The film’s supernatural elements arise naturally from the vicissitudes of isolation. Anyone locked in an apartment with some other vital people can testify to the febrile mind’s eye of too much contact with the circle of relatives and too little with the outdoor world.

At the beginning of the film, the circle of relatives talks about the Donner Party, when snowy American pioneers resorted to cannibalism. Cabin fever is in a completely different way in Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925), which he also partly promoted through the Donner Party. Here, the famine made Jim great, trapped in a snowy hut with the Lone Prospector (Chaplin), each perceived the other as a giant chicken, and attacked, fork and knife by hand.

Little Danny’s visions in The Shining, on the other hand, come from deprivation but from his ability to “shine,” to understand what is below, overlooked or in the future. Austere and terrifying photographs overwhelm him: ghostly dual sisters invite him to die; blood is flowing from an elevator (genocide?); an inversion of the word “murder” seems in a mirror — “redrum.”

Certainly, blocking can be a terrible experience. His version of SA, of course, is gender-based violence, which Jack carries out at the Overlook Hotel. But he’s still frustrated.

Would you like to comment on this article or see comments from other readers? Sign up (it’s fast and free) or log in now.

Read our comment before commenting.

Published through Arena Holdings and distributed with Financial Mail on the last Thursday of each Month of December and January.

Published through Arena Holdings and distributed with Financial Mail on the last Thursday of each Month of December and January.

© 2020 Arena Holdings. All rights are reserved.

Use of this is an acceptance of our terms and situations and our privacy policy.