Advertising

Supported by

Nonfiction

When you purchase a rating independently on our site, we earn a partner fee.

By Hector Tobar

SOUL PLEIN OF COAL DUSTA Fight for encouragement and justice in Appalachia through Chris Hamthrough

The troubled coal miners in Chris Hamby’s “Soul Full of Coal Dust” are a tough men’s organization, even if they may no longer have the role to play. After decades of running underground in the soot air of coal mines, many are severely disabled. They run out of breath after climbing a few steps, and some can only breathe with oxygen tanks that supply their lungs, day and night. X-rays show granular masses in the chest and spit black mucus, symptoms of pneumoconiosis, more commonly known as black lung disease.

Thanks to a federal law dating back to the 1960s, minors who contract the disease are entitled to monthly disability checks (usually less than $700) and a policy of all their medical expenses, unless the company that hired them says that the minors are not in poverty. health at all.

At Soul Full of Coal Dust, we find miners who have been fighting their employers for 20 years or more for those payments. They argue their case before administrative law judges or are represented through low-budget attorneys who are overtaken in legal battles with coal corporations and their tough lawyers. And yet their appalachian value is such that they continue the struggle, even as death approaches.

The key to them is to locate undeniable medical evidence of their disease. “Given his age and poor health, undergoing a lung biopsy would probably be too risky,” Hamby writes about Steve Day, 66, who denied the profits of his mining company. “This left another path,” Hamby wrote. He had told his wife to do an autopsy if he died.

After Day’s death, a pattern of tissue cut from his lungs presented the definitive proof: his paintings had killed him.

The clash of elegance in the United States is largely a utilitarian and domestic drama in those days. In the mountainous cities of Appalachia, as elsewhere, ordinary people are reluctantly fighting the strength of business and, more than anything, these struggles do not involve the drama of pickets, but rather piles of paper paintings. In “Soul Full of Coal Dust,” The Times reporter Hamby employs fierce research paintings and deep empathy for his subjects to bring this pathetic user to life. After following a long and miserable written trail, we nevertheless began to see a broader picture: how a corporate and political force design conspired to overwhelm the bodies of men who faithfully served the coal industry.

Most of the e-book is in West Virginia, where 68% of the electorate supported Trump in 2016, more than any other state. Today, the coal industry is a favorite child of the Trump administration, which has eased environmental restrictions on Big Coal, even when the world drowns with greenhouse gases. In 2017, a miners’ organization joined Trump in a rite at the White House for one of his first acts as president: signing a bill to reverse environmental regulations for coal mines.

It’s simple that the men and women who paint to produce coal were once a reliable democratic electorate. Laws designed to protect coal miners from black dust that saturates the underground air were born in the days of the blue state, a long time ago, as Hamby reminds us. In the early chapters of “Soul Full of Coal Dust,” the open-class warfare that explained appalachian history in the 20th century, with miners in a leading role, comes back to life.

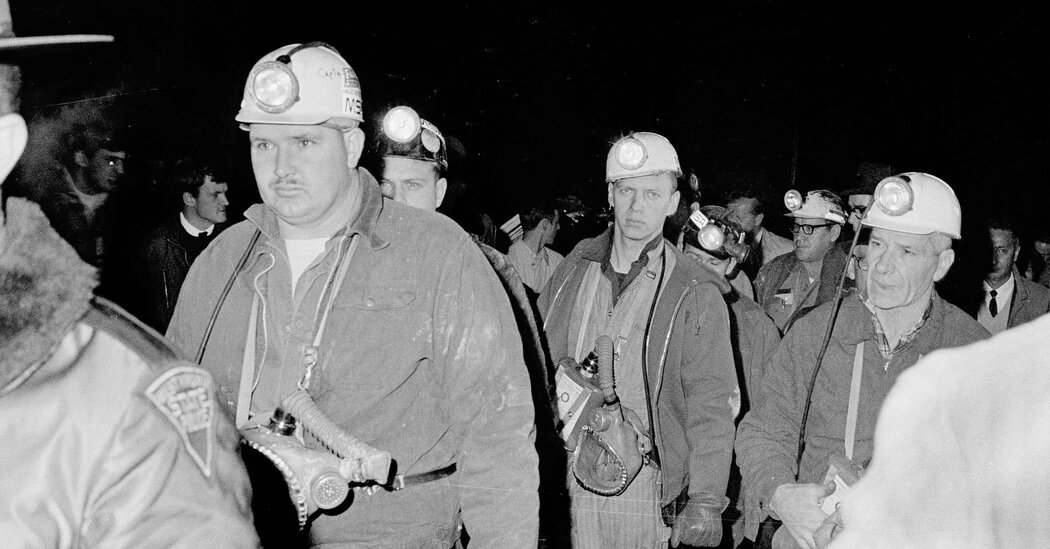

The turning point was the 1968 crisis at a mine in Farmington, West Virginia, 78 men died. Before Farmington, Hamby tells us, lung diseases that affected miners were shrouded in mystery, misinformation and folklore. After Farmington, clandestine racing situations have become a cause of fame. The I.E. Buff and other militant doctors have used the term “black lung” to dramatize the situation.

“Everyone has a black lung and everyone’s going to die!” Buff screaming at the miners’ rallies.

A coalition of miners, doctors and activists known as the Black Lung Association has begun pushing for comprehensive reforms, adding new reimbursement programs to staff. Miners wore banners at legislative hearings proclaiming “DO NOT DO. Soon, the motion reached the mines themselves, with a strike of two hundred employees in Raleigh County, southern West Virginia in 1969.”

“The news spread temporarily and within days, more than 10,000 miners from neighboring counties had joined the demonstration,” Hamby writes. “It was a savage strike; Control of United MineWorkers did not approve.” Some 40,000 West Virginia staff members temporarily participated in what Hamby called “the largest political strike in American history.”

After the “black lung lift,” West Virginia passed its first reimbursement legislation for staff with the disease; Kentucky and Ohio temporarily followed him. In 1969, Congress passed comprehensive reform that attacked the black lung as it originated by requiring corporations to particularly reduce (and often monitor) coal dust. Richard Nixon silently turned it into law; Unlike Trump, he did not invite coal miners to the firm’s rite because he didn’t have one.

The reforms were intended to eliminate the black lung, relegating it to the primitive beyond coal mining. But implementing legislation is another slower and much less visual struggle. At the dawn of the new century, the black lung grew again, while coal miners had jointly assimilated a worldview of the red state. Describing this new truth occupies most of Hamby’s book.

At first, the new generation of other people with black lungs, their disease is “the way of the world.” As one Hamby miner put it: “If he was looking to keep his task, he was executing when and how the company told him and didn’t complain.” And another: “If you were lucky enough to locate a task and had a circle of relatives to feed, you did what you had to do to feed your circle of relatives, sacrifice your body.”

Hamthrough is neither a sublime nor emotional writer, yet manages to capture the internal confusion of his subjects as they deteriorate and realize that mining corporations and their more sensible lawyers get the most out of it. Above all, it does so through a detailed description of repeated visits to the doctor and procedures before administrative judges.

“We weren’t lawyers. I didn’t know anything about the law,” said Mary Fox, the wife of miner Gary Fox, recalling the couple’s first spontaneous attempts to get black-lung bills. “We’ve never seen a courtroom before.” A lawyer stepped in to help the foxes: John Cline. After several frustrating years of running into a rural medical clinic and watching lawyers get the most out of West Virginia miners over and over again, Cline himself went to law school at the age of 53 just to set them up.

Through the eyes of Cline, Fox and others, we began to see how the formula is stacked: coal corporations are the tests that are meant to monitor coal dust underground; and the company’s lawyers hire competent doctors to respond to industry tenders, and add one at the prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital, Paul Wheeler.

As a journalist first attracted through the black lung saga, Hamthrough built a database of more than 3,400 X-rays tested through Wheeler, who rejected the black lung allegations of the more than 1,500 minors whose medical records he examined. Hamthrough’s paintings discredited Wheeler and eventually won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Research Reports. As an author, Hamthrough applies the same impfemability to chapters highlighting Cline’s failed attempts to prove that a West Virginia law firm participated in “judicial fraud”: the company’s lawyers had systematically concealed X-rays and medical reports that presented evidence of the disease.

At the end of “Soul full of coal dust,” we read as many profiles of lawyers, doctors, and judges as well as minors. All of this doesn’t make reading exciting. But the broader story of the courage of coal miners and the company’s misdeeds is eternal. With in-depth reports and an unlimited fear for his subjects, Hamby has created a hard document of this drama, which unfolds, largely invisible, in the hills and valleys of West Virginia.

Advertising