Consider this task offer:

A one-year contract to live and paint in China, fly, fix and manufacture airplanes. The salary is $13,700 according to the month with 30 days off per year. Accommodation is included and you will get an additional $550 depending on the month for the meal. In the most sensible way, there’s an additional $9,000 for every Japanese plane you destroy, no limit.

This is the agreement, in inflation-adjusted dollars of 2020, that a few hundred Americans reached in 1941 with the heroes, and some would even say that the Saviors, of China.

These American pilots, mechanics and workers’ corps have become members of the American Volunteer Group (AVG), later known as Flying Tigers.

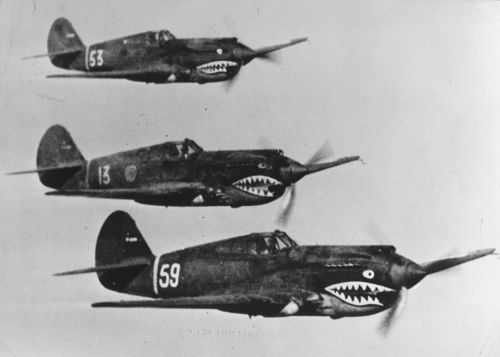

The group’s U.S.-made fighter jets had an open mouth filled with shark teeth on their noses, a fearsome aircraft still used in U.S. Air Force A-10 floor attack aircraft to this day.

The symbolic ferocity of the nose supported through its pilots in combat. The Flying Tigers are credited with destroying up to 497 Japanese aircraft with a load of 73 only.

Today, even with emerging tensions between the United States and China, these American mercenaries are still respected in China, with memorial parks committed to them and their exploits.

“China still remembers the contribution and sacrifice made to it through the United States and other World War II Americans,” reads on an access to the People’s Daily Online Flying Tigers Memorial page, administered by the Chinese state.

When these Americans arrived in China in 1941, the country very different from the China we know today. Leader Chiang Kai-shek, a revolutionary who broke away from the Communist Party, controlled to freely unite the country’s warlords under a central government.

By the last decade of 1930, China had been invaded by the armies of imperial Japan and suffered to resist its unified and supplied enemy. Japan virtually unopposed in the air, capable of bombing Chinese cities at will.

In the face of this terrible situation, Chiang’s government hired US-based Claire Chennault, a retired U.S. army captain, to form an air force.

He spent his early years working to establish a precautionary network against airstrikes and build air bases in China, according to the official Flying Tigers website. Then, in 1940, he was sent to the United States, still an impartial World War II party, to locate pilots and aircraft that could protect China as opposed to the Japanese Air Force.

With smart contacts in the management of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and a budget that can pay Americans up to 3 times what they can earn in the U.S. military, Chennault can get the flyers he needed.

Planes were a little bigger problem. The United States manufactured them in gigantic quantities, but they were meant for Britain to be used in opposition to Germany or for American forces, amid fears that the war in Europe would soon triumph in the United States.

An agreement has been reached to send a hundred Curtiss P-40B fighters built for Britain to China. Due to its difficulties, Britain has been promised a new and greater style about to move to the meeting line.

In his memoir, Chennault wrote that P-40s purchased in China lacked some features, adding a fashion viewer.

“The wrestling record of the First American Volunteer Group in China is even more remarkable because its pilots pointed their weapons through a raw, handcrafted, ring and post gun viewfinder of the most accurate optical attractions used through the Air Corps and the Royal Air Force,” he said. Writes.

What was missing from the P-40’s capability, Chennault tactically made it, causing AVG pilots to launch from a higher position and drop their weapons from heavy devices onto structurally weaker but more maneuverable Japanese aircraft.

In low, tortuous and rotating air combat, the P-40 would lose.

Chennault’s teaching pilots were far from the flower and cream of the harvest.

Ninety-nine airmen, along with staff, made the holiday to China in the fall of 1941, according to the history of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Some had just graduated from flight school, others were flying seaplanes or pilots of giant bomber ferries. They signed up for the Far East adventure to make a lot of money, to lose girlfriends or simply because they were bored.

Perhaps the best-known of the Flying Tigers, U.S. Navy aviator Greg Boyington, around whom the “Black Sheep Squadron” television screen founded in the 1970s, was there for the money.

“Having gone through a painful and guilty divorce from an ex-wife and several young children, he had ruined his credits and incurred a really large debt, and the Marine Corps had ordered him to submit a monthly report to his commander on how he explained his pay to pay those debts,” according to a U.S. Department of Defense’s record of the group.

With such a disparate organization of pilots, Chennault had to teach them how to fight the pilots, and fight in teams, necessarily from scratch.

Education was rigorous and lethal. First, three pilots died in accidents.

On a day without getting married, 8 P-40s broke because the pilots landed too hard or the floor team drove too fast, causing collisions. In one case, a mechanic on another twist of fate crushed his bike against a hunter, damaging his wing. There were so many twists of fate that day, November 3, 1941, that AVG called it “Circus Day”.

Chennault expressed his sadness at his group’s first fighting project opposed to Japanese bombers attacking AVG base in Kunming, China, on December 20, 1941. He thought the pilots had lost their field in the excitement of the fight.

“They tried to almost shoot and then agreed that only luck had prevented them from crashing or shooting,” the Ministry of Defence’s account reads.

However, they shot down at least 3 Japanese bombers, wasting a fuel-free fighter and crashing.

AVG pilots temporarily conquered their steep learning curve.

A few days after Kunming, they were deployed to Yangon, the capital of British colonial Burma and an important port for the line of origin carrying Allied warplanes to Chinese troops opposed to the Japanese army.

Japanese bombers came to the city in waves for 11 days on the Christmas and New Year holidays. The Flying Tigers have dug holes in Japanese formations and consolidated their reputation.

“In 11 days of combat, the AVG had officially launched 75 enemy aircraft from the sky with an undetermined number of probable deaths,” the group says. “Avg’s losses were two pilots and six aircraft.”

The Flying Tigers spent 10 weeks in Yangon, surpassed by the Japanese all along, inflicted staggering losses on Tokyo forces.

In his memoirs, Chennault points out what his organization, which has never covered up more than 25 P-40s, has achieved.

“This small force faced a total of a thousand Japanese aircraft over southern Burma and Thailand. In 31 encounters, they destroyed 217 enemy aircraft and destroyed 43. Our combat losses were 4 pilots killed in the air, one killed by firearm and one captured prisoner. Sixteen P-40s were destroyed,” he wrote.

The U.S. Military takes note of heroic acts on the ground:

“Team leaders and technicians performed improvisation miracles to prepare fighters to fly, but if one (of the planes) … would have been on U.S. Army bases, would have been considered highly unlikely to fly,” he said.

Despite the Heroism of the Flying Tigers in the air, Allied floor forces in Burma were unable to contain the Japanese. Yangon fell in late February 1942 and the AVG retreated north to the interior of Burma.

But they had gained significant time for the Allies’ war effort by immobilizing Japanese aircraft that may have been used in India or China and the Pacific.

According to Chennault, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill made this comparison:

“These Americans’ victories over Burma’s rice fields are comparable, if not in their magnitude, to those won through the Royal Air Force (RAF) on the Kent hops fields at the Battle of Britain. Chennault quotes Churchill.

Although the news did not come temporarily in 1941-42, the United States, still recovering from the devastating attack through the Japanese on December 7, 1941, opposed to Pearl Harbor, was hungry for heroes. The Flying Tigers do the trick.

Republic Pictures cast John Wayne for the title role of “Flying Tigers” in 1942. Posters from the films showed a P-40 in attack mode and a promotional photo shows Wayne’s status near one of the P-40s. On screen, Wayne plays the first of his many war hero roles, Captain Jim Gordon, inspired by Chennault.

“The story doesn’t have much to do with genuine history, and a lot of old propaganda after Pearl Harbor fills the script,” his review says in Amazon.com.

Wayne’s official Facebook page says manufacturers have made sure the film, one of the greatest hits of 1942, doesn’t show war secrets.

“No scene of the interior of the aircraft can be displayed for protection reasons. The panels shown were wrong,” he says.

While Republic Pictures was busy with the film, AVG’s Washington sponsors asked Walt Disney to create a logo.

Disney artists have invented “a winged Bengal tiger that jumps over a stylized symbol of the “V of Victory,” America’s history says.

It would possibly be unexpected if the logo didn’t come with the iconic shark mouth that appears on the Flying Tigers plane.

Chennault wrote that the shark’s mouth did not come from his group, but that it had been copied from the British P-40 fighters in North Africa, who in turn would have copied them from the German Luftwaffe.

“How do you derive the term Flying Tigers from the P-40s with shark nose?” he wrote.

When the United States went to war after Pearl Harbor and began looking for tactics to carry out the fight in Japan, the concept of an experienced organization of American fighter pilots operating under Washington seduced U.S. army leaders. They sought the Flying Tigers to be compared to the U.S. Army Air Corps.

But the pilots themselves sought to return to their original state (many came here from the Navy or The Marine Corps) or sought to remain as civilian contractors of the Chinese government, where the salary was much better.

Most told Chennault that they would quit smoking before doing what Washington wanted. When the army threatened to recruit them as infantrymen if they did not volunteer, those who logged in withdrew.

Chennault, who had been officially considered an adviser to the Central Bank of China while in command of the AVG, was appointed brigadier general in the United States Army and agreed that the Flying Tigers would form a United States Army team on July 4, 1942.

Although the Flying Tigers continued to wreak havoc on the Japanese in the spring of 1942, reaching ground targets and aircraft from China to Burma via Vietnam, it is clear that the force is entering its final days, according to the history of the U.S. military.

AVG completed its project on the day it ceased to exist on July 4.

Four Flying Tiger P-40s fought a dozen Japanese fighter jets over Hengyang, China. The Americans shot six of the Japanese at any loss, according to American history.

With today’s industry wars and the military’s provocative training in the Pacific in recent years, the United States and China are in a downward spiral.

But under those headlines, the bond that American mercenaries forged with China about 80 years ago remains intact.

In May, the Chinese consulate in Houston donated $11,000 worth of food to a hospital in Monroe, Louisiana, home to the Chennault Air Force and Army Museum, as the medical center fighting the coronavirus pandemic.

“Although there are many ‘winds against’ in China and the United States. Today, China has never hesitated for a moment that friendship between the peoples of our two nations will ever change,” a letter from the Chinese consul general accompanying the donation reads.

Also in May, the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China sent doctors to the Flying Tiger Historical Organization to distribute to their members, friends and family of Flying Tigers veterans, according to an article from Xinhua Press Service.

In China, flying Tigers tributes are important.

The Xinjiang basketball team has followed the term as its nickname, there are at least a dozen museums or exhibits committed to Flying Tigers in China and have been the subject of new movies and cartoons.

Ma Kuanchi helped identify Flying Tiger Heritage Park at a former Guilin airfield where Chennault once had his command post in a cave.

Ma met with two Americans to create the Flying Tiger Historical Organization, which cooperated with the Beijing government to fund, build and manage Guilin Park, which opened in 2015.

Last year, Ma told Chinese television channel CGTN what he considers the legacy of U.S. citizens who went to China in 1941.

“The Flying Tiger is one of the non-unusual grounds of the Rose Garden in the United States and the Great Hall of the People in China. We would like to appreciate the spirit of the Flying Tiger for mutual respect, sacrifice, determination and mutual understanding. To locate non-unusual terrain, the two wonderful nations will have a more wonderful future,” Ma said.

In the United States, the Louisiana Museum’s online page carrying Chennault’s call summarizes what he hoped his legacy would be the most sensible thing on his homepage, the last lines of the general’s memoir:

“I sincerely hope that the flying tiger’s signal will remain in the air as long as it is obligatory and that it will be remembered on both sides of the Pacific as the symbol of two wonderful peoples who run for an unusual purpose in times of war and peace.”

Terms of the privacy policy

KVIA-TV FCC Public Archive

Don’t sell my information